kirsten kaschock

Rather than transcribing lived experience directly, I choose to make strange the almost-familiar. Why? Because we also need the ineffable.

Rather than transcribing lived experience directly, I choose to make strange the almost-familiar. Why? Because we also need the ineffable.

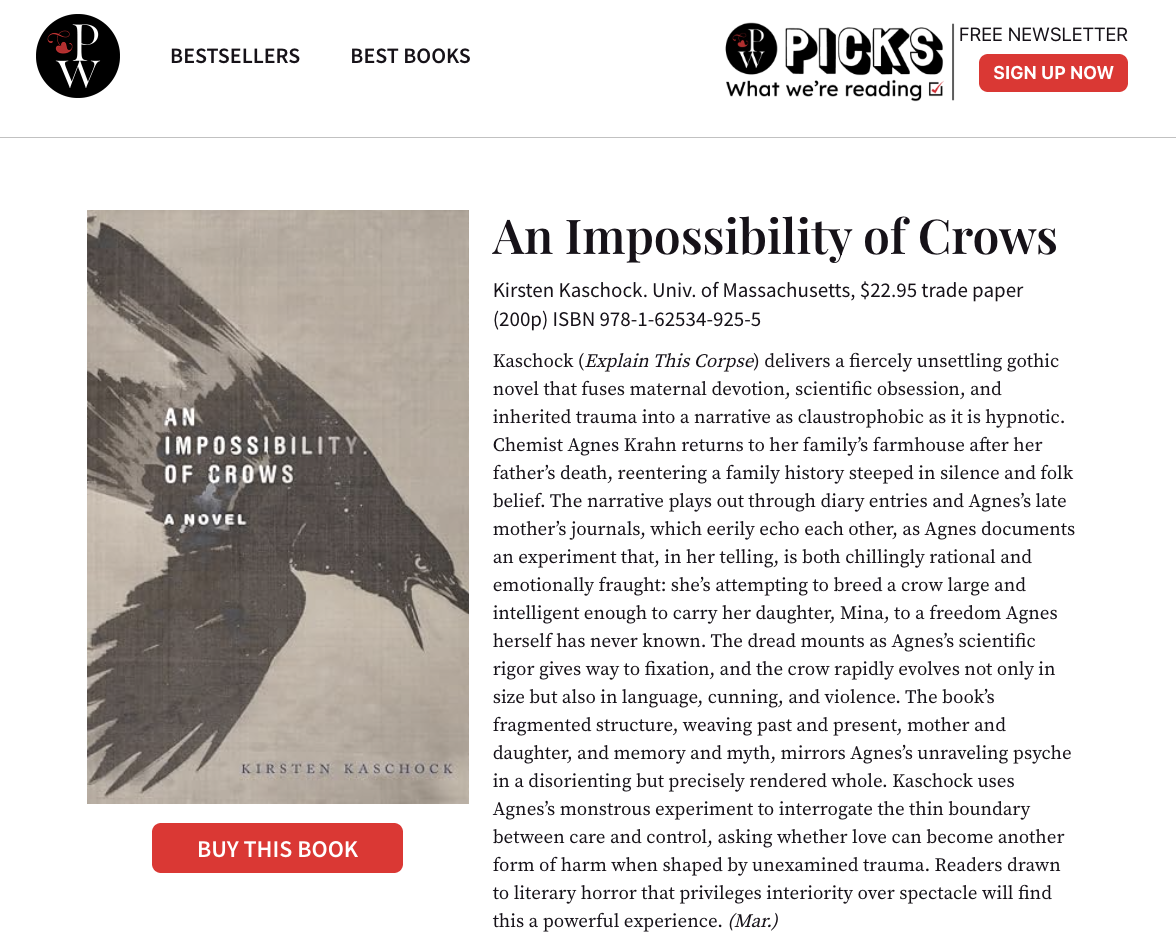

Publishers Weekly Pre-publication Review 12.24.2025

—short story—

The girls returned to us are not girls. They were taken at eleven and returned at seventeen. Forty-six were taken and fourteen returned. Had they then expired, were they no longer of use to them who had done the taking? In the morning, we woke and they were here, in the center of the village. And we do not know what to do.

…read more at Fence Magazine

—poem—

If it kills you, you’ve gone too far

The sea, I mean. If you walk out into

its maw without thought, you will die.

I don’t care what kind

of swimmer you are—and it’s the same

with children. I was one, then

had one. What else to do? There’s too much

pain for mastery, but it does make the work

better. It makes the self more evident

in the work when you’re gulped-down

breastmilk in other spheres…

…read more at Poetry

—essay—

In a single body, there hide any number of childhoods. Maturity, I think, is a myth. And time—an illusion made impossible to treat as illusion by aging… Our bodies’ housing of other bodies (fetuses and tumors alike) fosters still other kinds of delusion: immortality, cessation. Bourgeois knew this. She refused to let her own work travel in only one direction. She redrew the same line drawings dozens of times over decades. A famous installation of her architectural sculptures at the Tate Modern was titled I do, I undo, I redo. Her spirals, whether enormous staircase or tiny shell, point out over and over again that time and growth do not move as we perceive them to.

Maggots know this also.

…read more at Bennington Review

The poet become an entire, imperiled landscape, poked with death and sex and literature and philosophy. Crawling with them, as is the world. “Must I be so outside I’m theoretical?” she asks. In Kaschock’s particular, hard-nosed alchemy, her poems use elements of language as tools to contort her very poetic self, until the voice becomes a body, twisting, leaping, into flight.

How limitless, how tangible, how strange.

Read the rest of the review, by Leah Claire Kaminski, HERE

I choose to make-strange the almost-familiar. Why? Because we also need the ineffable. My work takes the uncanny as breadcrumb strategy. When it succeeds, my poetry has given body to something just-shy of speech. When my work fails, it has juxtaposed ideas too stepmother-y to treat as kin. I love my failed poems. They are working further into the woods than I can yet say. They are eating the witch.

(more at the The Pew Center for Arts & Heritage)